As a change-up from audiobooks, I’ve lately been listening to a fair number of podcasts. While working my way through the back archives of one show, I was struck by a dreadful piece of synthesized harpsichord music used to introduce one of the segments. That is to say, it was a perfectly pleasant Baroque passage, but the rendering was, well, heinous.

While the synthesis of instruments has greatly advanced since the seventies, the person who coded up that harpsichord wasn’t even trying. Worse, there were some seriously infelicities of timing, where whoever was playing the keyboard had stumbled slightly.

All of the above might be tolerated for a repetition or two, but after the twelfth or so I was contemplating ripping my (or perhaps someone else’s) ears off. Still, distressing as the synth harpsichord was, I had a worse source of dismay: I could not identify the composer.

The piece was extremely familiar, but I couldn’t slot it into any of my memories. Bach? Telemann? It was light and familiar, could it perhaps be Mozart? My recall system was coming up with nothing useful.

Clearly, surfing through PDFs of musical scores was not going to be an efficient system of identification. There’s been quite a bit of work done around automatically identifying particular recordings, such as that which resulted in the unfortunate publicity for the husband of late Joyce Hatto (he had been passing off other artists’ recordings as hers).

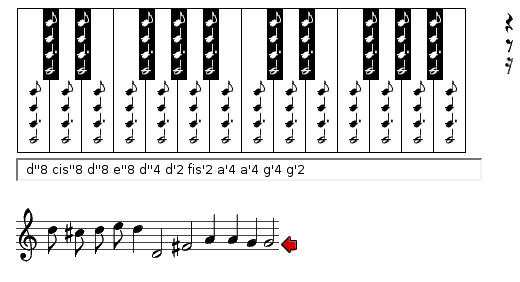

Unfortunately, I was working from a one-off synth rendering, so that approach was out. Let’s see, it goes da-da-deedle-DAH-DAH-DAH-dah-dah-dah-dah. What can I do with that?

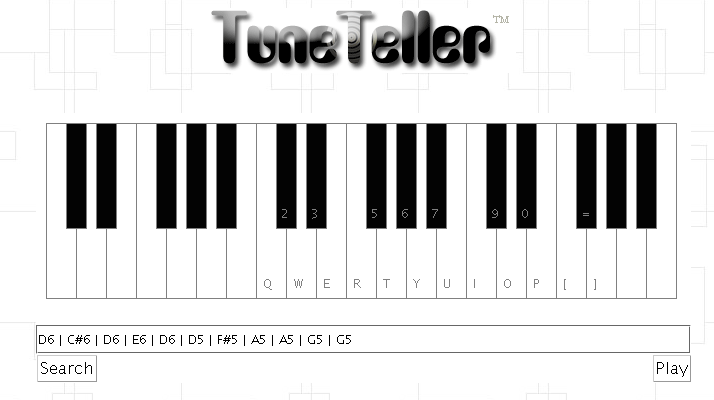

It turns out, rather a lot. With the right website, you can leverage the memory a melody into an identification. I found two sites that profess to identify music from a few notes: Musipedia and TuneTeller.

Musipedia.org

I didn’t have good luck with Musipedia, which was far too optimistic in its matching. Its number-one suggestion (“The Poker Party Polka”) was not exactly what I remembered. Nor was it “Blowin’ in the Wind”, nor Verdi, nor Schubert, nor Bartók, nor any of the next fifty suggestions. Musipedia was clearly not going to cut it. I did try some of other forms of searching (contour and rhythm searches) without success. Interestingly, they do have a “sing or whistle” search, but I was disenchanted with Musipedia by that point.

TuneTeller.com

On the other hand, TuneTeller popped it up on the second try. The first time, it complained because I had entered too much of the melody; it apparently works best with just a few bars. Moments later, I had my answer: it is a minuet by Luigi Boccherini; in fact, just about the only piece he wrote which is still at all well-known.

Thanks to the Internet, I can sleep at night.

M—— often reproves me for a habit she finds reprehensible: reading while in the bathroom. I shall not be moved. The mind can be engaged even as Nature is answered.

M—— often reproves me for a habit she finds reprehensible: reading while in the bathroom. I shall not be moved. The mind can be engaged even as Nature is answered. (Never fear, part 2 of “

(Never fear, part 2 of “